Note: Experience tells me I must start with the disclaimer that I admire Apple but I am not a Macaholic or a Windows Geek. I don’t care who has the better OS except to the extent that it provides examples for successful or poor innovation.

Apple! Apple! Magazines can’t possibly be wrong so Apple is clearly the Most Admired, the Most Innovative, and the Master at Design.

Let me tell you, when what you teach and develop every day has the title Innovation attached to it, you reach a point where you tire of hearing about Apple. Because everyone believes the equation Apple=Innovation is a fundamental truth akin to the Second Law of Thermodynamics, Boyle’s Law, or Moore’s Law. But ask these same people if they understand exactly how Apple comes up with their ideas and what approach they use to develop such blockbuster products and whether it is a fluky phenomenon or based on a repeatable set of governing principles and you mostly get a dumbfounded stare. This is what frustrates me because people worship what they don’t understand.

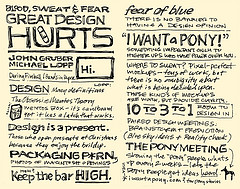

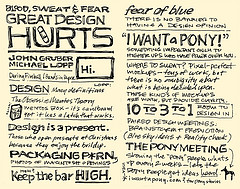

I’ve been meaning to write this post for some time but finally sat down and put pixel to screen after coming across a description of Michael Lopp’s (a Senior Engineering Manager at Apple) discussion of how Apple does design during the panel he did at SXSW Interactive with John Gruber (yes for you Apple heads, that Daring Fireball guy) on March 8th titled Blood, Sweat, and Fear: Great Design Hurts. I know, you’re saying, It’s been 13 days Alain, how slow can you be? Well, I was waiting for someone to post an actual recording of the seminar but neither video nor audio seems to exist at this point. If someone reads this and happens to have such a recording please, please, share!

What will follow then is a collection of insights that various attendees created from their notes of attending and then my own personal discussion of what this portends for people who aspire to be like Apple. My intention is to attempt to synthesize what various attendees have written into a single representation of what Lopp and Gruber actually said.

Helen Walters at BusinessWeek summarized Lopp’s panel with five key points:

Apple thinks good design is a present. Lopp starts off this section by discussing of all things, the story of the obsessive design of the new Mentos Box. You know Mentos right? The really odd packaging (paper rolls like Spree candy)Â promoted by some of the most bizarre ads on TV? It’s the candy that nobody I know eats, they just use it to create cola geysers. Have you looked recently at the new packaging Mentos comes in? Why did they change the packaging from a roll to a box? I’ll do a post on this later but if you want to read about it here’s an article from 2003 discussing the rationale for the change. Lopp says the new box is a clean example of obsessive design because the cardboard top locks open and then closes with a click – there’s an actual latch on the box and it actually works. It’s not just a square box but one that serves a function and works. I went out and bought a box just so I could examine it more closely and it’s an ingenious design of subtle simplicity that works so well even shaking it upside down does not pop the box open.

According to John Gruber, the build-up of anticipation leading to the opening of that present is an important (if not the most important) aspect of the enjoyment people derive from Apple’s products. The world divides into two camps:

- Those who open their presents before Christmas morning

- Those who wait – they set their presents under the tree and like a child agonize over the enormous anticipation of what will be in the box when they open it on Christmas morning

Apple designs for #2. No other company is so heavily fetishized in the online unboxing photo documentation phenomenon. But few companies put as much attention to detail as Apple does to the fit and finish of the box let alone the out of box experience. How many companies do you know that make packaging p*rn? And you can capture that Christmas morning experience more than once a year with every stop you make at the local Apple store. Apple wraps great ideas inside great ideas and the whole experience is linked as the present concept traces from the bottom up: Apple’s OS X operating system is the present waiting inside its sleek, beautiful hardware; its hardware is the present artfully unveiled from inside the gorgeous box; the box is the present waiting for your sticky little hands inside its museum-like Apple Stores; and the bow tying it all together? Steve Jobs’s dramatic keynote speeches, where the Christmas morning fervor is fanned on a grand stage by one of the business world’s most capable hype men.

Pixel perfect mockups are critical. This is hard work and an enormous amount of time but is necessary to give the complete feeling for the entire product. For those who aren’t familiar with the term this means the designers for a piece of software at Apple create an exact image down to the very pixel (the smallest point of light on your monitor – it is the basic unit of composition on a computer or television display) for every single interface screen and feature. There is no Ipsum Lorem used as filler for content either. At least one of the Senior Managers refuses to look at any mock-ups that contain such Greek filler. Doing this removes ALL ambiguity – everyone knows and can see what the final product will look like and critique it accordingly. It also means you won’t get changes by the designer or engineer after the review as they are filling in the content – something I have seen happen time and time again. Ultimately it means no one can feign surprise when they see the real thing later on.

10 to 3 to 1. Take the above concept and pile on top of it the requirement that Apple designers expect to design 10 different mockups of any new feature that is considered. And these are not just crappy mockups, these all represent different but really good implementations that are faithful to the product specifications. Then narrow these down to 3 based on specific criteria that the team spends months further developing until they finally narrow down to 1 final concept that truly represents their best work for production. This approach is intended to offer enormous latitude for creativity that breaks past restrictions. But it also means they inherently plan to throw away 90% of the work they do. I don’t know many organizations for whom this would be an acceptable ratio. This is a major reason why I say you can’t innovate like Apple.

Paired design meetings. Every week the teams of engineers and designers get together for two meetings.

- Brainstorm meeting – leave your hang-ups at the door and go crazy in developing various approaches to solving particular problems or enhancing existing designs. Free thinking with absolutely no rules.

- Production meeting – The absolute opposite of the brainstorm where the aim is to put structure around the crazy ideas and define the how to, why, and when.

These two meetings continue throughout the development of any application and if you know the stories of Steve Jobs discarding finished concepts at the very last minute you will understand why the team operates in this manner. It’s part of their corporate DNA of grueling perfection. But the balance does shift away from free thinking and more toward a production mindset as the application progresses even while they keep the door open for creative thought at the latest stages.

Pony meetings. These meetings are scheduled every two weeks with the internal clients (AKA God himself and his minions) to educate the decision makers on the design directions being explored and influence their perception of what the final product should be.

They’re called “Pony” meetings because they correspond to Lopp’s description of the experience of Senior Managers dispensing their wisdom and wants to the development team when discussing the early specifications for the product. “I want WYSIWIG…I want it to support major browsers…I want it to reflect the spirit of our company.” [What???] In other words, I want a pony. Who doesn’t want a pony? A pony is gorgeous! The issue that anyone who has sat through these types of experiences can tell you [we do it all the time in our senior management interviews as we develop a strategic vision for new product development] is that these people are describing what THEY think THEY want. Lopp cops to reality in explaining that since they are signing the checks you cannot simply ignore these senior managers, but you do have to manage their expectations and help align their vision with the team’s.

The meetings achieve this purpose and give a sense of control to senior management so that they have visibility into the process and can influence the direction. Again, the purpose of this is to save the team from pursuing a line of direction that ultimately gets tossed because one of the decision makers wasn’t bought in.

Now, if you want to get the quick summary of what we just discussed, I highly recommend reading Mike Rohde’s SXSW Interactive 2008 Sketchnotes. He took highly illustrated notes of the Lopp/Gruber panel. Content for this write-up also came from: Scott Fiddelke, Dylan at The Email Wars, Jared Christensen, David at BFG, and Tom Kershaw.

What else does Apple do differently? If you read the various interviews that Steve Jobs and Jon Ive have given over the last few years you’ll find a few specific trends.

1. Apple does not do market research

This is straight from the man’s mouth: We do no market research. They scoff at the notion of target markets and they don’t conduct focus groups. Why? Because everything Apple designs is based on Steve and team’s perception of what THEY think is cool. He elaborates further:

It’s not about pop culture, and it’s not about fooling people, and it’s not about convincing people that they want something they don’t. We figure out what we want. And I think we’re pretty good at having the right discipline to think through whether a lot of other people are going to want it, too. That’s what we get paid to do. So you can’t go out and ask people, you know, what’s the next big [thing.] There’s a great quote by Henry Ford, right? He said, ‘If I’d have asked my customers what they wanted, they would have told me “A faster horse.” ‘

Said another way, Steve hires really smart people and he lets them loose on a leash since he overlooks it all with an extremely demanding eye. If you’re seeing visions of the “Great Eye” from J.R.R. Tolkein’s books then you probably wouldn’t be too far off. Here’s the way their simple process works:

- Start with a gut sense of an opportunity and the conversations start rolling…

- What do we hate? (Our cellphones)

- What do we have the technology to make? (A cellphone with a Mac inside)

- What would we like to own? (An iPhone, what else?)

But Jobs also explained that in this specific conversation, there were big debates across the organization on whether or not they could and should do it. Ultimately, he looked around and said, Let’s do it.

I think it’s clear they also benefit with the inauspicious leak out to the market – and by that I mean I think this overly tight-lipped organization occasionally leaks early ideas out to the market to see what kind of response they might generate. Again, what other company benefits from having thousands of adoring designers who come up with beautifully photoshopped concepts of what they think the next great product should look like?

2. Apple has a very small team that designs their major products

Look at Jonathan Ive and his team of a dozen to twenty designers who are the brains behind the genius products that Apple has delivered to the market since the iMac back in 1998. New product development is not farmed out across the organization but instead is creatively driven by this select group. Here’s how one journalist described them:

“Apple is a cult, and Apple’s design team is an even more intense version of a cult,” notes Riley. Actually, it’s not a big cult — just a dozen people or so. But they operate at an extremely high level, both individually and as a group. Ive has said that many Apple products were dreamed up while eating pizza in the small kitchen at the team’s design studio.

It’s a team that has worked in idyllic comfort for many years. Some designers were at the company long before Ive arrived in 1992. They rarely attend industry events or awards ceremonies. It’s as though they don’t require outside recognition because there isn’t any higher authority on design excellence than each other, and because sharing too much information only risks helping others close the gap. And they personally reflect the design sensibilities of Apple’s products — casually chic, elitist and with a definite Euro bent. The team, made up of thirty- and fortysomethings, has a definite international flair. Members include not only the British Ive but also New Zealander Danny Coster, Italian Daniele De Iuliis, and German Rico Zorkendorfer. “Its good old-fashioned camaraderie — everyone with the same aim, no egos involved,” says British fashion designer Paul Smith, a friend since the late 1990s when Ive sent him a new iMac. “They have lots of dinners together, take lots of field trips. And they’ve turned these gray frumpy objects called computers into desirable pieces of sculpture you’d want even if you didn’t use them.”

Most of Ive’s team live in San Francisco, and rumor has it that the starting salary for the group is around $200,000, some 50% above the industry average. They work together in a large open studio with little personal space but great privacy. Many Apple employees aren’t allowed in, for fear they’d catch a glimpse of some upcoming product. A massive sound system pumps up the music. Ive invests his design dollars in state-of-the-art prototyping equipment, not large numbers of people. And his design process revolves around intense iteration — making and remaking models to visualize new concepts. “One of the hallmarks of the team I think is this sense of looking to be wrong,” said Ive at Radical Craft. “It’s the inquisitiveness, the sense of exploration. It’s about being excited to be wrong because then you’ve discovered something new.”

Ive’s team at Apple isn’t the usual design ghetto of creativity that exists inside most corporations. They work closely and intensely with engineers, marketers, and even outside manufacturing contractors in Asia who actually build the products. Rather than being simple stylists, they’re leading innovators in the use of new materials and production processes. The design group was able to figure out how to put a layer of clear plastic over the white or black core of an iPod, giving it a tremendous depth of texture, and still be able to build each unit in just seconds. “Apple innovates in big ways and small ways, and if they don’t get it right, they innovate again,” says frog design founder Hartmut Esslinger, who designed many of the original Apple computers for Jobs. “It is the only tech company that does this.”

Jobs himself has delegated away many of his day-to-day operational responsibilities to enable him to focus half of his week on the high and very low level development efforts for specific products.

3. Apple owns their entire system

They are completely independent of reliance on anyone else to provide inputs to the design and development of their products. They own the OS, they own the software, and they own the hardware. No other consumer electronics organization can easily do what Apple does because they own all of the technology and control the intimate interactions that ultimately become the total user experience. There is no other way to ensure such a seamless experience – a single executive calls the final shots for every single component.

Jobs says this question of control is critical to Apple’s success:

I’ve always wanted to own and control the primary technology in everything we do. Take audio. For years, the primary technology was the [marking mechanism] inside a CD or a DVD player. But we became convinced that software was going to be the primary technology, and we’re a pretty good software company.

So we developed iTunes [Apple’s music jukebox software that later morphed into the iTunes Music Store]. We’re a good hardware company, too, but we’re really good at software. So that led us to believe that we had a chance to reinvent the music business, and we did.

4. Apple focuses on a very select group of products

Apple acts like a small boutique and develops beautiful artistic products in a manner that makes it very difficult to scale out to broad and extensive product lines. Part of this is due to the level of attention to detail provided by their small teams of designers and engineers. To think that a multi-billion dollar company only has 30 major products is astounding because their neighbors at that level of revenues have thousands of products in hundreds of different SKUs. As Jobs explains, this is the focus that enables them to bring such an extensive level of attention to excellence. But it is also an inherently risky enterprise because they are limited in what new product areas they can invest in if one fails.

“Apple is a $30 billion company, yet we’ve got less than 30 major products. I don’t know if that’s ever been done before. Certainly the great consumer electronics companies of the past had thousands of products. We tend to focus much more. People think focus means saying yes to the thing you’ve got to focus on. But that’s not what it means at all. It means saying no to the hundred other good ideas that there are. You have to pick carefully.

I’m actually as proud of many of the things we haven’t done as the things we have done. The clearest example was when we were pressured for years to do a PDA, and I realized one day that 90% of the people who use a PDA only take information out of it on the road. They don’t put information into it. Pretty soon cellphones are going to do that, so the PDA market’s going to get reduced to a fraction of its current size, and it won’t really be sustainable. So we decided not to get into it. If we had gotten into it, we wouldn’t have had the resources to do the iPod. We probably wouldn’t have seen it coming.”

5. Apple has a maniacal focus on perfection

They say that Steve Jobs had the marble for the floor at the New York Apple store shipped to California first so he could examine the veins. He also complained about the chamfer radius on the plastic case of an early prototype of the Macintosh. You had better believe, given the 10 to 3 to 1 approach for design, that every shadow, every pixel is scrutinized. It’s in their DNA. They are willing to spend the money to make sure everything is perfect because that is their mission. Just as an example, when Jonathan Ive and team developed the original iMac they wanted to give the colored plastic shell on the back a crystalline look:

To understand how to make a plastic shell look exciting rather than cheap, Ive and others visited a candy factory to study the finer points of jelly bean making. They spent months with Asian partners, devising the sophisticated process capable of cranking out millions of iMacs a year. The team even pushed for the internal electronics to be redesigned, to make sure they looked good through the thick shell. It was a big risk for Jobs, Ive, and Apple. Says one rival: “I would have had to prove that transparency would increase our sales, and there’s no way to prove that.” He figures Apple spends as much as $65 per PC casing, vs. an industry average of maybe $20.

So is it possible for you to innovate like Apple?

Now, given all of this, what is a company to do if they want to innovate like Apple? First, forget about it unless you are willing to invest significantly and heavily to establish a culture of innovation like Apple has. Because it’s not just about copying Apple’s approach and procedures. The vast majority of executives who say, I want to be just like Apple, have no idea what it really takes to achieve that level of success. What they’re saying is they want to be adored by their customers, they want to launch sexy products that cause the press to fall all over themselves, and they want to experience incredible financial growth. But they generally want to do it on the cheap.

To succeed at innovation as Apple has you need the following:

You need a leader who prioritizes new product innovation.The CEO needs to be someone who looks out on the horizon and consistently sets a vision of innovation for the organization that he/she is willing to completely support with people, funds, and time. Further, that leader needs to be fluent in the language of your customer and the markets you compete in. If the CEO cannot be this person then they need to be willing to invest that role into a senior executive and give them the authority and latitude to effectively oversee the new product development process.

Jobs explains it this way:

You need a very product-oriented culture, even in a technology company. Lots of companies have tons of great engineers and smart people. But ultimately, there needs to be some gravitational force that pulls it all together. Otherwise, you can get great pieces of technology all floating around the universe. But it doesn’t add up to much. That’s what was missing at Apple for a while [during the 11 year period between 1985 and 1997 while he was gone]. There were bits and pieces of interesting things floating around, but not that gravitational pull.

People always ask me why did Apple really fail for those years, and it’s easy to blame it on certain people or personalities. Certainly, there was some of that. But there’s a far more insightful way to think about it. Apple had a monopoly on the graphical user interface for almost 10 years. That’s a long time. And how are monopolies lost? Think about it. Some very good product people invent some very good products, and the company achieves a monopoly.

But after that, the product people aren’t the ones that drive the company forward anymore. It’s the marketing guys or the ones who expand the business into Latin America or whatever. Because what’s the point of focusing on making the product even better when the only company you can take business from is yourself?

So a different group of people start to move up. And who usually ends up running the show? The sales guy. John Akers at IBM (IBM ) is the consummate example. Then one day, the monopoly expires for whatever reason. But by then the best product people have left, or they’re no longer listened to. And so the company goes through this tumultuous time, and it either survives or it doesn’t.

You need to focus. A cohesive vision needs to be established that describes the storyline for your products and services. That storyline needs to decisively state what is in bounds and what is out of bounds over an 18 month to 3 year period. Everyone who matters to the development process needs to be in lockstep with this vision which means you need to have open lines of communication that are regularly and consistently managed. This storyline or strategic vision needs to be revised according to market changes and the evolution of your new product pipeline. It helps that Apple tends to approach their products with a systemic frame of mind, looking to develop the “total solution” rather than just loosely joined components.

Again, here is how Jobs describes their approach:

And it comes from saying no to 1,000 things to make sure we don’t get on the wrong track or try to do too much. We’re always thinking about new markets we could enter, but it’s only by saying no that you can concentrate on the things that are really important.

He continues the thought by describing that they focus on two things and the first one is to create the best products available whether its PCs, or phones, or music players or online media stores:

We don’t get a chance to do that many things, and every one should be really excellent. Because this is our life. Life is brief, and then you die, you know? So this is what we’ve chosen to do with our life. We could be sitting in a monastery somewhere in Japan. We could be out sailing. Some of the [executive team] could be playing golf. They could be running other companies. And we’ve all chosen to do this with our lives. So it better be damn good. It better be worth it. And we think it is.

Obviously, the other focus is to make a profit since that is what supports the continued efforts to design the next great product. And when every one of the major products is a moonshot, they have to work to ensure it meets exacting standards to do everything they can to ensure success.

You need to know your customer and your market. Steve Jobs and team can get away with not doing market research, identifying target markets, or going out and talking with customers because of the markets they play in and the cult-like customers who adore them. Most technology companies believe they can get away with this and most technology companies get it wrong. Quick, identify 10 different pieces of technology that truly understood and met your needs and don’t bug you due to a major flaw that you either have to live with or compensate for in some fashion. Could you come up with more than five? I didn’t think so. We’re drowning in a sea of technological crap because every product that is released to the market is a result of multiple compromises based on decisions made by the brand manager, the R&D product manager, the marketing manager, the sales manager and everyone else who has skin in the game as they prepare the offering to meet what THEY think the target customer’s needs are.

The reason Jobs and Jonathan Ive get it right is because they design sexy products with elegant and simple interfaces for themselves and count on their hip gaggle of early adopters to see it the same way. Once the snowball starts rolling, it’s all momentum from there. Apple doesn’t sell functional products, they sell fashionable pieces of functional art. That present you’re unwrapping is all about emotional connection. And Steve Jobs knows his marketplace better than anyone else.

Because you’re not Apple and you are likely not selling a similar set of products, you must do research to understand the customer. And while I’m sure Steve says he doesn’t do research, it’s pretty clear that his team goes out to thoroughly study behaviors and interests of those they think will be their early adopters. Call it talking to friends and family, but honestly you know that these guys live by immersing themselves in the hip culture of music, video, and computing.

The point is not to go ask your customers what they want. If you ask that question in the formative stages then you’re doing it wrong. The point is to go immerse yourself in their environment and ask lots of why questions until you have thoroughly explored the ins and outs of their decision making, needs, wants, and problems. You should be able to break their need or opportunity down into a few simple statements of truth.

As Alan Cooper says, how can you help an end user achieve their goal if you don’t know what it is? You have to build a persona or consumer model that accurately describes the objectives of your consumer and the problems they face with the existing solutions. The real benefit, as I saw in my years working at InstallShield and Macrovision, is that unless you put a face and expectations on that consumer, then disagreements on features or product positioning or design come down to who can pull the greatest political will rather than who has the cleanest interpretation of the consumer’s need.

You need the right people and to reward them accordingly. The designers at Apple are paid 50% more than their counterparts at other organizations. Now these guys aren’t working at Apple simply because they’re paid more. They stay at Apple because of the amazing things they get to do there. Rewards are about salary and benefits, but they are also about recognition and being able to do satisfying work that challenges the mind and allows the creative muscles to stretch. Part of this also comes down to ensuring your teams are passionate about innovation and dedicated to the focus of the organization. As Jobs says, he looks for people who are crazy about Apple. So you need to look closely at who you are hiring and whether you have the right people in the organization in the first place.

It’s not much, but I’ve only begun to carve out what it takes for you to succeed at developing “perfect” products like Apple does. And honestly, their products are far from perfect. But that’s a post for another day.